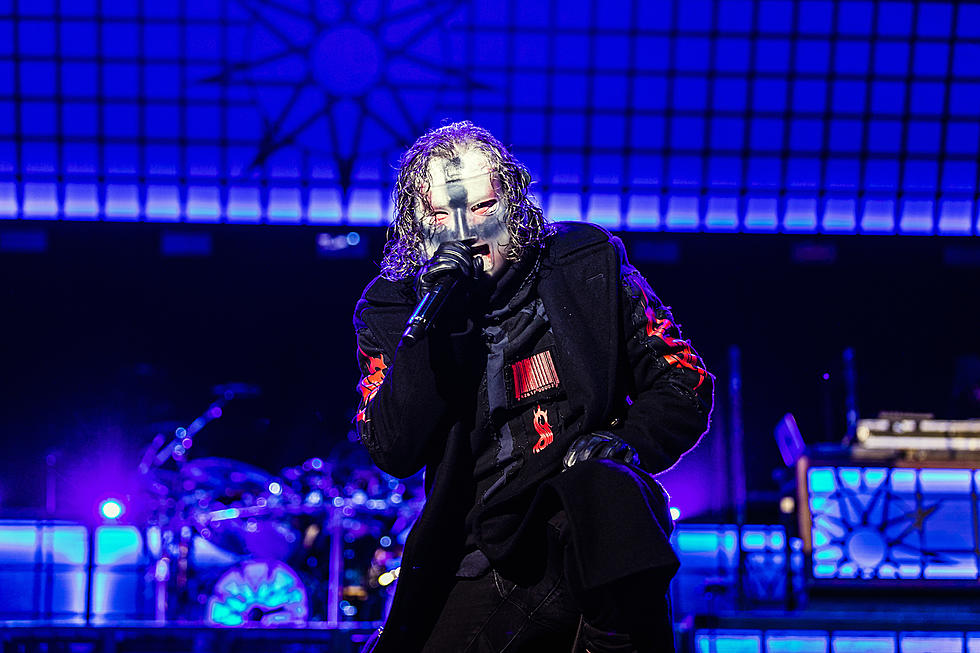

Interview: Slipknot’s Corey Taylor Once Again Embraced Pain to Create Unflinching Art

When Slipknot released the crushing, commanding .5: The Gray Album in 2014, label executives fans and maybe even band members breathed a collective sigh of relief. Once again, the Knot proved that they were survivors. They had lived through the death of bassist Paul Gray and the departure of drummer Joey Jordison and created an honest, turbulent tribute to their fallen comrade. The adversity kept on coming.

The band spent a solid three years writing their wildly eclectic new album We Are Not Your Kind. Part of the reason the album took them so long was because they wanted to create the record they had been envisioning for more than a decade. They’ve shown time and time again that they can deliver the HEAVY. And they’ve demonstrated that they can blend complementary and contrasting vocal melodies and growls with a variety of truculent beats and trenchant and textural guitar styles. What they’ve never done — until now — is craft a full-length, cohesive, near-narrative album as driven by offbeat experimentation into the realms of prog rock, soundtrack music, industrial, avant garde and even ‘80s pop.

It’s understandable that it would take an established band years to make an album that tapped into their past strengths while catapulting them into a future unbordered by expectations or restrictions. The reasons it took almost five years from the release of .5: The Gray Album to the launch of We Are Not Your Kind are complicated. Slipknot didn’t want to race the clock when it came to art. But, perhaps more significantly, some of the band members were dealing with debilitating and devastating personal issues.

For frontman Corey Taylor, the scars ran so deep he had to take about 18 months to try to make sense of the collapse of his relationship with second wife Stephanie Luby, who he married in 2009 and separated from in 2016. Between the emotional damage he sustained during the marriage and the soul-searching he underwent to rebuild himself in the aftermath, Taylor was in a state of self-loathing and desperation when he started writing lyrics for We Are Not Your Kind.

The words that spilled from his brain and onto his laptop were vicious, vitriolic and seemed to tell the painstricken story of how a dysfunctional marriage led Taylor to question everything he once believed in and threatened not only his wellbeing but his very identity.

With all the textural and atmospheric instrumentals, segues, intros and midsections, We Are Not Your Kind feels like a concept album, but that was never Slipknot’s intent. They wanted to create, not a thematic piece, not a collection of singles, but a full, cohesive album to be listened to from start to finish — the kind of record they would have cherished when they first became obsessed with music.

At the end of the day, what matters is not how critics or even fans interpret the album, but that everyone in the band is stoked with the collection of diverse and emotional songs they’ve created. And what should matter to the Maggots is that as Slipknot approach their 35th anniversary as a band, they’re as ambitious, artistic and expressive as they’ve been in more than a decade. Despite recent personal traumas and the departure of longtime percussionist Chris Fehn, the Knot continue to dominate the scene, evolve as musicians and they haven’t lost a smidgen of the hunger and hubris that first got them noticed way back when Anders Colsefni was singing for the band and Taylor was still working behind the front desk of a porn shop in Iowa.

You’ve said this was not meant to be a concept record. Was there a point in the process when you thought, “Yeah, maybe this is a concept album?”

Not at all. To be honest, we were just trying to make an album. The narrative really came from me working my way through the repercussions of a really toxic relationship. And the fallout that came with finally extricating myself from that relationship. So, I didn’t realize there was a linear message going on until we all sat down and listened to it and that made it feel like a story. Even Clown said, “I’m listening to this like it’s a concept album.” And I’m like, “Yeah, but it’s not.” It’s really weird. It’s one of those things where it’s accidentally linear, but it really wasn’t supposed to be weird in a Tarantino sense.

Art doesn’t exist in a vacuum and what a lyricist is going to write about if he or she is sincere is going to reflect the recent emotional experiences he or she has had.

When I hone my focus it really intensifies the purpose with which I attack it. I don’t know if that’s a good thing or not. This was the first time in a long time that we were able to go into a studio and not feel like there was a certain type of album we were supposed to make.

When we did All Hope is Gone we were just really lucky to get an album out of that because of all the turmoil that was going on in the band at the time. There are some great, great songs on that album. But cohesively, it just wasn’t there. And then .5 was us going, “God, do we even want to do this anymore?” It was almost a rediscovery. It didn’t have the same kind of urgency as our earlier albums.

Again, there were great songs, but it didn’t have that same energy that we were trying to capture. And it’s only in retrospect when you really start listening to stuff back to back that you realize that, “Yeah, man there was something there.” And maybe it’s because there was a mournful vibe to it that it had that.

Do you go into the songwriting process for We Are Not Your Kind knowing that this had to be wildly diverse and experimental?

We walked in realizing that we had carte blanche again; we could do whatever we wanted. It was the same vibe we had with Vol. 3: The Subliminal Verses. And bringing that same kind of energy in really meant that we could go anywhere with the music and as long as we were happy with it, we knew it was gonna be fuckin’ awesome.

The first words on the album are “I’m counting all the killers.” Who are the killers?

It’s a metaphor for counting all the ways that you’ve been minimalized, marginalized — all the things that have been laid on you like an issue and the things that have been laid on you like a scapegoat. You’re counting all the things that are slowly killing your identity.

For All Hope Is Gone you recorded most of the album in the main studio and then a few of you worked on more experimental, atmospheric songs in a second studio. Very little of that stuff emerged. But it seems like that artistic approach planted the seeds for the experimentation on We Are Not Your Kind.

The funny thing about All Hope is Gone is that it was a power struggle, basically. Without naming names, I was stuck in the middle. It was almost like being a friend of the Montagues and the Capulets, for Christ sakes. I was standing in the middle going, “Uh, what’s going on here? Why can’t we at least pull some of these threads to knit this together?”

I actually put together a mix of songs from both houses that really worked. There were six songs from each session and there was a really cool, atmospheric, amazing version of All Hope is Gone that was rejected outright by a couple of people in the band. It was really sad for me. It was very much a case of take your toys and go home. And it made life miserable in that band for a while. As much as we were trying to make an album, it seemed like everyone was trying to make their album, and it was heartbreaking. And then you fast forward to .5 and we’re just trying to pick up the pieces and see what happens.

What was the impetus to break boundaries for We Are Not Your Kind?

We were all very much of the mindset where we went, “Okay, no one’s trying to force us into a certain mindset or a certain direction. Let’s get back to where we were. Let’s get back to that point where we can craft these amazing moments and knit them together with these heavy, heavy songs – these frenetic fucking bursts of energy. And let’s draw on all of these influences that we’ve had for so long and that we hinted at with Vol. 3 but that we’ve never been able to let really shine and let them off the chain.

I feel like this album follows that spirit even more than Vol. 3. I think Vol. 3 has some great songs on it and it has a wider field, while We Are Not Your Kind is just so fuckin’ dark that it’s compelling in a way that Vol. 3 never was.

Volume 3. was monumental in a different way. It seamlessly integrated melody with brutality and included an asylum’s worth of tortured emotions. By contrast, We Are Not Your Kind doesn’t seem to strive for commercial acceptance. The wide range of melodies and hooks work because they’re integral to the songs they’re in, not because they offer something radio can latch onto.

We made this record because this is the record we wanted to make. We had vignettes like “What’s Next?” coming out of our ears because we were looking for intros and just different things to add to the songs. And then, obviously, there’s “My Pain.” I can hear that in a movie, for fuck’s sake. The composition and the scoring of it is just insane. It’s visceral, it’s thick, it’s heavy. But then it’s this whole other realm of crazy. There’s almost a Stanley Kubrick kind of vibe to it.

Was it an agonizing to write and record We Are Not Your Kind? Were there a lot of disagreements over where to go with the songs?

No, man. This was actually a joy to put together. Even the difficult times when we were trying to figure out musical passages like mathematical equations, we were all just stoked to be making music and doing what we were built to do. It was really cool, and it was good to feel that way again.

What was the first song you worked on where you mixed all these different sonic elements – soundtrack music, metal, industrial, classic rock – together into the same sonic gumbo? Was it the Rolling Stones-esque choir in the first full song, “Unsainted?”

The funny thing about that is that “Unsainted” was actually the last song we finished. We had recorded it a couple different times and hadn’t really found the spirit yet. It wasn’t until Clown and [producer Greg Fidelman] started talking about this grandiose intro with the choir that it was then re-recorded with a little more urgency. It was really cool how it came together.

I wasn’t sold on the choir at first. They kept referencing The Stones’ “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” which is one of my least favorite Stones songs. It just goes off the deep end of pretense. But what they did with the choir gave me chills when I first heard it. That song was the perfect punctuation mark for what the album was going to be. It was that missing element that we needed for the album.

Did you have a structured work formula for the songs? For example, did you record the songs in bits and pieces until they were full compositions and then to add all the frills later?

The band would get together in big bursts and they would record the music live, basically. And then I would come in and do the vocals. So that’s why the heavy stuff has such a great urgency to it. It has that live feel that makes it killer. And then there was some stuff we would fuck around with and build in the studio bit by bit until all the layers were right.

Was there a song that made you feel like the multifaceted approach you were taking with the music was solidifying into a unified work of art?

The first song that made me feel like we were doing something different again was “Spiders.” That song wasn’t tracked in a typical way. The core of it was recorded and then we kept adding elements to it. We had all these songs around it that we were tracking and finishing, but we were constantly looking for the key to “Spiders.” We were looking for the moments to add to it. It was almost like seasoning a stew. Too much and it doesn’t work, just the right amount and it’s damn near perfect.

Did anyone ever feel like you were going too far with “The Exorcist” theme song intro or the Queen-esque handclaps? It’s not exactly your “Radio Ga-Ga” but it’s a leap into the unknown.

The thing that’s most interesting to me about that song is that there are no rhythm guitars on it. There are moments that feature guitars, but there’s no real bedrock that you get with a normal Slipknot song.

There’s something about the starkness of it so that when those little elements come in – and those elements only happen once in a while during the song – they’re these sparse ear candy moments that make the song what it is. There’s never too much all at once. You get just enough.

Was there any conflict when Jim Root and Mick Thomson figured out there wasn’t going to be guitar riff driving the song?

No, no, no. It was the opposite. Mick was reluctant to put guitar on it. He said, “This is awesome the way it is.” He thought there might already have been too much going on there. So we had to find ways to add those elements that didn’t overdo it or make it overbearing. The guitar solo has got a strong hint of Adrian Belew, which I thought was perfect. It had that element of David Bowie on “Fashion.”

It’s not the only song with a hint of Bowie on it.

Exactly. When you’re going, go all the way. Basically, that was the approach we wanted to take for the whole album. For me, we had to have all these different kinds of elements that knit everything together. You couldn’t have just one song like “Spiders.” You couldn’t have just one song like, “Insert Coin,” this intro that builds toward entering this machine [that] will then send you through this rollercoaster ride of emotion. We had to have elements all through.

“Insert Coin,” “What’s Next” and “Death Because of Death” all act as little independent segues but what makes the album more than a killer metal disc with a few interludes is the atmospheric, textural and downright weird parts that swim in and out of the rest of the tracks.

We were working with all kinds of experimental parts. We cut “Death Because of Death” down to make it even more poignant. A song like that can go too long, but if you find the right moments in it you’ve really got something.

You mentioned Bowie before. “A Liar’s Funeral” has a touch of “Space Oddity” in it as well as other unexpected moments.

That is my favorite song on the album, by far. To me it’s like what David Bowie would do if he did a black metal song. There’s so much atmosphere and so much poignancy and impact. When I lay those vocals down when we did the demos for it, Clown and Jim sat up at attention. They were like, “Holy shit!” And for me, that’s the best kind of reaction I could have gotten. If I can throw them for a loop I know I’ve got something, because they’ve heard me do everything. So when I hit them with something that they’re not expecting, that’s amazing.

The whole album is dark, but there’s something about “A Liar’s Funeral” that’s even bleaker than the faster, angrier stuff.

Oh yeah, man. That song is so lamenting and so real that it was destined to be this moment on the album. It’s pretty rad, and I’m so happy that it came out the way it did.

You were in a difficult period entering this album, which can be completely devastating. Loss and depression can drain creativity or make artists want to lie in bed for weeks or drink themselves into the abyss. Did you suffer through any of that or was it the exact opposite. Did you immediately dig into your art to purge yourself off all the negativity?

Here’s the thing: When I got out of that relationship it was euphoria at first because it was hard. It was hard stepping away. I had done everything I could to make it work. Once I got to the point where I realized there was no way it was going to work I had to step away for my own self-preservation.

So, getting away was so freeing and there was a real sense of happiness for a second. And then the repercussions of that relationship came back on me. And I realized that I had a lot of issues that I had to figure out for myself, physically and mentally. I had to go back to therapy, I had to reexamine who I was as a person. I had to reexamine what made me happy.

I’m not gonna unpack it all, I’ll just say it took me at least a year to feel good about myself. It was tough. But I also knew I had a lot to say. And, honestly, it was almost kismet that we were doing a Slipknot album. I don’t know if I could have done it with a Stone Sour album.

To get rid of this emotional bile that I had been choking on for a long time and this sense that I wasn’t good enough for anything, I needed a Slipknot album. It took letting that out to realize that I had been through hell. And maybe that’s why I feel okay now and I can listen to this album and say, “Jesus Christ.” There was a lot that needed to be said. I hope everybody enjoys it, because it was hell to live through.

It seems that Slipknot pulls all the stops when the shit hits the fan. Unfortunately, your pain is the Maggots’ gain. Or maybe it works both ways and the devastating power of Slipknot is a tool for all of you to vent your baggage and the reaction of the audience is irrelevant?

That’s it exactly. It’s a catharsis. It’s therapy. It’s our family gathering together to support one another.

One of the most brutal songs on the album is “Solway Firth,” on which you went all-out with the confessional lyrics: “While I was learning to live, we all were living a lie / I guess you got what you wanted / So I will settle for a slaughterhouse soaked in blood and betrayal / It’s always somebody else… somebody else was me. You want the real smile or the one I used to practice, not to feel like a failure?”

It’s actually the last line of the song that is the most revealing: “You want a real smile? / I haven’t smiled in years.” That’s the one that is probably the most real thing I’ve ever written. And that in itself is the story of a man who has had to walk a line and put on that face even in the light or shadow of dealing with not only outside issues, but inside issues.

[It addresses] dealing with depression and having to lie and say that everything’s fine when everything isn’t. I’ve dealt with physical and clinical depression my whole life. And then when you’re in a situation that actually exacerbates the situation and not only makes it worse, but you’re made to feel like it’s not true and that you have to deny it because they don’t want to admit there’s an issue. That’s even worse.

Now you find yourself in this spiral in which you can’t even say that you’re hurting because no one’s listening. When everything that happens is made to feel like it’s your fault then what do you get right? So that last line is the album closer for a reason. Clown heard it and told me, “That’s what needs to be the last sentiment that is spoken on this album.” And I was like, “Alright.” I didn’t realize until we put the album together that he was absolutely right.

“Not Long for This World” is chilling enough as a lyrical expression, but knowing it comes from someone who has battled severe depression is unsettling because maybe it’s too real in a horrible way. You sing, “So decide / Tell me how I’m gonna die / ‘Cause I’ve already gone away.” And surely that’s you railing against the forces of opposition that you’ve now escaped. But maybe people once said that about dismal lyrics from Chester Bennington or Chris Cornell?

You have to share those feelings. If you don’t, then that’s when they fester. That’s when they become something uncontrollable. At least when you share those feelings you make them malleable. You give them weight. You give them something that you can grasp onto. Now you can deal with it.

Repression is the quickest way to destroy yourself. It always has been. And for me, I’ve always been able to talk about what was going on with me – at least in a certain sense – so I’ve always been able to get to the heart of a problem, no matter what. And it’s tough. Dealing with those issues is tough.

But at the same time, if I can put it out there relate with people and get across the idea that we all fight those kinds of depression and darkness. If I can put that out there and show people that it is not a singular thing. It’s not something you should wear like a stigma. And if that helps one single person then it’s mission accomplished.

Loudwire contributor Jon Wiederhorn is the co-author of Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal, as well as the co-author of Scott Ian’s autobiography, I’m the Man: The Story of That Guy From Anthrax, Al Jourgensen’s autobiography, Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen and the Agnostic Front book My Riot! Grit, Guts and Glory.

Slipknot's 'We Are Not Your Kind' is out Aug. 9. Catch the Knot on tour by getting tickets here.

See Slipknot in the 50 Most Important Metal Bands in the 21st Century

More From Noisecreep